You know the saying “To make an omelette, you have to break a few eggs?” Well, to make a pastel painting you have to break a few sticks.

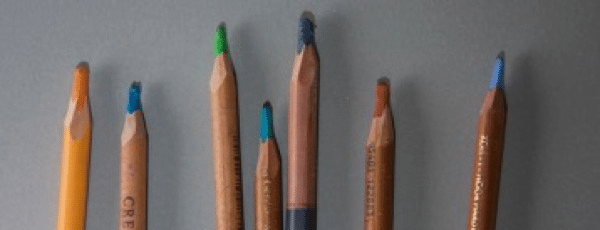

The commission that I finished required being able to precisely add marks to the faces in tiny strokes. The temptation would be to break out the pastel pencils and sharpen them to death. Squeak, squeak… and then use them to kill the painting. I have mentioned before that I do not sharpen my pastel pencils that way. Rather, I “block cut” them like below…

I just grab an xacto knife and roughly cut them down leaving a blocky, squared-off point. I don’t care about needle-sharp fine points. Who has time for that? Plus, if I am painting that tiny, then I am not doing myself any favors. Painting that tiny is like walking down the street in a skirt that is way too tight. So restricting. And then it feels pinched in the work. Nope, if I am using pencils it is in a rather wilder, cross-hatch mode and it is for layering only. Preferably in the early stages and then I move on to thicker sticks.

Besides, I don’t really use pastel pencils much in my faces. Why? I have talked before about the powers of pastel in past articles:

– https://swannportraits.com/the-power-of-pastel-in-action/

– https://swannportraits.com/power-of-pastel-with-christine-swann/

– https://swannportraits.com/the-power-of-pastel/

– https://swannportraits.com/powers/

In short, pencils have a ton of binder in them. Simply, this dilutes the color. So, if you think you can get a glowing, rich portrait by using only pastel pencils, think again. It can’t be done. It is like painting with a child’s cheap set of watercolor paints. A pastel pencil may look bright pink, but it is actually very watered-down color. So putting a black pastel pencil into the eyes of your portrait will not make them “black”… think about it. It is watered down and will not be true black. The black will be as soggy as a mud puddle. In pastel, true black has very little binder.

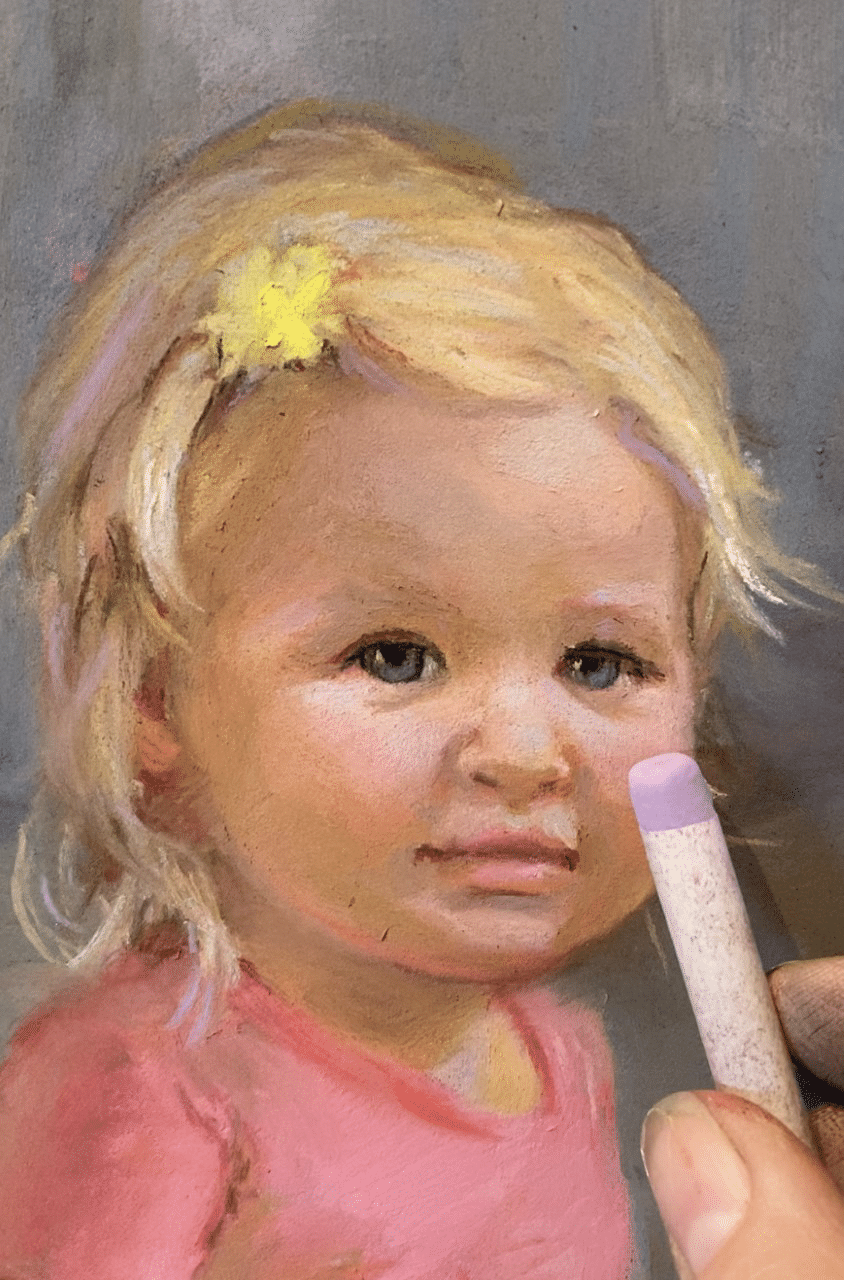

Using progressively more saturated pigment where you need it is key. This means bigger sticks that have less binder in them so that the color is more saturated. This means breaking your sticks to get smaller marks. Some of you are cringing, but I would rather break my good sticks to get precise marks than have my sticks look “oh so pretty” in the box and not be able to control them. If you are not breaking your sticks and using the sharp corners from the break – no matter what brand – then you are not putting your tools to their best use. I routinely break my Roche pastels, and if you are not familiar, these are $20 a stick.

On this painting I also used some very, very old Giraults that I found on Ebay a few years ago. I actually contacted the Girault company to ask about them since I had never seen sticks like these before. The company said they were from the 1930’s-1940s. (imagine using sticks from around the time of WWII! It is a humbling feeling to use sticks this old) They are very tiny sticks that have a small amount of binder in them considering how small they were made. Since they are so much smaller than regular sticks they were very helpful for detailing the features.

Here are the old Girault sticks against a more normal-sized Sennelier pastel stick. Yup, they are pretty tiny which is great since they leave a very fine line. I love this tiny box of history. But what good would they be if I just left them on a shelf?

And don’t be afraid to truly make marks on your painting. The “blendy- blendy” thing pastellists can fall into is contrite and looks stiff and as though a young high-schooler did the work. Make a deliberate mark. Add another slightly different-colored mark beside it and keep going. Many layers will blend them naturally and be more realistic than smudging things around. Make clear marks. If they are off, make them again. Yes, I know, a pain, but portraiture is precision. Good mark-making is what a painting is all about anyway.

Break a stick! Break a stick! Make it your mantra! Put your sticks to work and don’t worry about how they look or how you will keep them pretty in a box. All that matters is putting them to work.

I hate to deface my beautiful pastels. But, I agree that you cannot get the full force of what these sticks of pigment can do when they are papered and fat. LOL I have some that are no more than fingernail size. Still vibrant, still useful, Still in my kit. Thanks for your advice. I always listen.

yay! 😁

Christine, You have made my heart skip a beat. I have an old Girault box given to me by a friend. Her artist aunt had the box in her attic. I knew there were at least a few Girault pastels inside, as those were wrapped in paper labelled “Girault Pastels” and “France.” However, there were also numerous mystery pastels, including 15 or so smaller pastels wrapped in unlabelled paper. Unknown origin until I saw your photo. They look EXACTLY like yours. Same length and diameter, same size paper. They even feel like Giraults. You have made my day!

yay! Treasure in the attic! They are very sweet and I love using them.

P.S. I also love your post. Great message about markmaking and breaking sticks to make them more useable. I do that, too, and encourage my students to do the same. –Keep painting and keep writing your great advice.

thanks! will do!

This is a big help thanks ,

sure! 😁

Funny you should write about pastel pencils. I use to use them on occasion, but would get so frustrated because if you dropped it, odds are it was shattered inside. Effectively, useless! I read a tip about using, for example, Nupastels. Carve a chisel point on one end, and you could use it for a fine point or slightly broader swath. I don’t need it often, but it works.

yes, and Creatacolor uses the exact colors and recipes in their sticks as they do in their pencils. I use them a lot for the same reason. But I do love pencils and use them a lot!

Good Grief! As one who uses a great deal of skill to achieve beautifully blended skin tones, I never thought that the award-winning portraits I paint would be characterized as a “blendy-blendy” thing pastellists can fall into” and “contrite and stiff and as though a young high-schooler did the work.”

hehe. Don’t take it personally. Just noting that many artists strive for blending pastels and it kills the image. If it works for you, then great. but it can become cutesy.

I just hit up your site. And yes, using more deliberate and thoughtful mark-making will elevate your work. And get more awards if that is your goal. Good luck with it!

Oh dear, I don’t actually disagree with you but i love working with a handful of pencils. And i have never sharpened a pencil with a knife and not broken it. It embarrassing to ask how to sharpen a pencil.

hi. Actually I use the pencils a lot! Most of my pastel paintings are comprised of pencil work. Just not in the details like you would think. Otherwise it defeats the purpose of focus.

more wisdom from you! always appreciated. i hope you’re doing well

doing great! 😁